Thursday, August 18. 2011

The crucial question is who are we as a people? From my personal experiences I note three prominent characteristics that are typically Pinoy.

The first one is the strong family and clan “connectedness”. Pinoys may find themselves in the remotest part of any continent or in the middle of the ocean; they may live in foreign lands for years and even centuries; yet they always find their way home, the Philippines.

But the Philippines, for most Pinoys, is not the group of islands now called the Republic of the Philippines. It is first and foremost the kin and kith – the ancestors, the clan and the family. Home is in their hearts and blood.

The powerful symbol of this ‘connectedness’ is the world famous “balikbayan boxes for ‘pasalubong’. At airports everywhere, balikbayan boxes are marks of Pinoys ‘coming home’. But these boxes also traveled by all kinds of couriers – accompanied or not - they all go to the Philippines as if the whole world is being “delivered” to the motherland box by box.

The movement is also two-way. Pinoys also “import” their closest kin and kith the very moment they get their legal papers. They begin petitioning them one at a time and soon they build a small barangay or network of kinfolks in their adopted land.

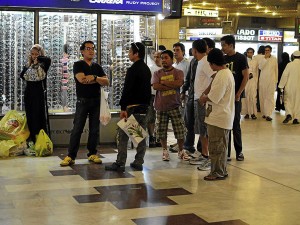

Second to family and clan is, believe it or not, patient work and discipline. You find Pinoys doing all kinds of jobs and odd jobs. They work and they are NOT beggars and they pay their taxes. In many instances, Pinoys have dual jobs and they still work on weekends! They obey rules and they are good citizens notwithstanding the Philippines’ notoriety for “palusot” and "connection".

But the real miracle is the fact that notwithstanding difficulty and hard work, they are happy. There is always a smile on their faces and there is laughter in their lives that they can even make jokes out of their tragedies! Pinoys are a happy people and a happy nation even in moments of passing insanity.

The third is faith and tradition. Pinoys are known for their belief and traditions. The Visayans bring their Santo Niño; the Tagalogs their Nazareno; Bicolanos their Peñafrancia; the Ilocanos their Santa Lucia; the Pampangos their Pedro and Santiago, and Zamboangeños their Nuestra Señora del Pilar, etc. They, too, have their Pasyon, Visita Iglesia and Misa de Gallo. These faith and tradition are uniquely Pinoys and they have become not only the soul but also the bulwark of strength against adversities and challenges, in foreign lands.

Today people admire Mother Theresa or Oscar Romero or Martin Luther King Jr. or Desmond Tutu or Nelson Mandela, or our very own Cory Aquino not because of their achievements but for the values and beliefs they stood for. They believed and lived with integrity and no embarrassment.

In similar vein, Pinoys will endure. And they are recognized by their fidelity to the values and traditions they stand for. These three values are family, joyful hard work and their faith & traditions.

Pinoys, notwithstanding the difficulties they've face, have found a way to successfully write their story line. It is the story of their family, tribe and clan. It is a “kindredness” shaped not only by blood, but also by the “ili” – the community and eco-system. And Pinoys are darn proud of their story and they share it with the world with a smile on their faces and joy in their hearts.

The first one is the strong family and clan “connectedness”. Pinoys may find themselves in the remotest part of any continent or in the middle of the ocean; they may live in foreign lands for years and even centuries; yet they always find their way home, the Philippines.

But the Philippines, for most Pinoys, is not the group of islands now called the Republic of the Philippines. It is first and foremost the kin and kith – the ancestors, the clan and the family. Home is in their hearts and blood.

The powerful symbol of this ‘connectedness’ is the world famous “balikbayan boxes for ‘pasalubong’. At airports everywhere, balikbayan boxes are marks of Pinoys ‘coming home’. But these boxes also traveled by all kinds of couriers – accompanied or not - they all go to the Philippines as if the whole world is being “delivered” to the motherland box by box.

The movement is also two-way. Pinoys also “import” their closest kin and kith the very moment they get their legal papers. They begin petitioning them one at a time and soon they build a small barangay or network of kinfolks in their adopted land.

Second to family and clan is, believe it or not, patient work and discipline. You find Pinoys doing all kinds of jobs and odd jobs. They work and they are NOT beggars and they pay their taxes. In many instances, Pinoys have dual jobs and they still work on weekends! They obey rules and they are good citizens notwithstanding the Philippines’ notoriety for “palusot” and "connection".

But the real miracle is the fact that notwithstanding difficulty and hard work, they are happy. There is always a smile on their faces and there is laughter in their lives that they can even make jokes out of their tragedies! Pinoys are a happy people and a happy nation even in moments of passing insanity.

The third is faith and tradition. Pinoys are known for their belief and traditions. The Visayans bring their Santo Niño; the Tagalogs their Nazareno; Bicolanos their Peñafrancia; the Ilocanos their Santa Lucia; the Pampangos their Pedro and Santiago, and Zamboangeños their Nuestra Señora del Pilar, etc. They, too, have their Pasyon, Visita Iglesia and Misa de Gallo. These faith and tradition are uniquely Pinoys and they have become not only the soul but also the bulwark of strength against adversities and challenges, in foreign lands.

Today people admire Mother Theresa or Oscar Romero or Martin Luther King Jr. or Desmond Tutu or Nelson Mandela, or our very own Cory Aquino not because of their achievements but for the values and beliefs they stood for. They believed and lived with integrity and no embarrassment.

In similar vein, Pinoys will endure. And they are recognized by their fidelity to the values and traditions they stand for. These three values are family, joyful hard work and their faith & traditions.

Pinoys, notwithstanding the difficulties they've face, have found a way to successfully write their story line. It is the story of their family, tribe and clan. It is a “kindredness” shaped not only by blood, but also by the “ili” – the community and eco-system. And Pinoys are darn proud of their story and they share it with the world with a smile on their faces and joy in their hearts.